Conversations with Behjat Sadr

by Narmine SadegExtract from the publication Behjadt Sadr. Traces, Paris, Zamân Books, 2014.

The conversations reproduced in these pages stem from several encounters that took place during the summer of 2001. At first, they were just friendly dialogues, but very soon we saw the interest in transcribing them. We re-examined several passages many times while adding new questions. This interview became a pretext for many discussions that do not appear in the final version. Both Behjat Sadr and I took a large amount of notes. She enjoyed these conversations and was fully involved with them. An abridged version was released in 2002 as a homemade, limited-run publication, and an extract was included in the catalogue for Behjat Sadr’s 2004 exhibition at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.

Recently, while working on an archive of her writings, I found a list of themes and questions I had given her at the beginning of the interview in order to provide her with a survey of the subjects we were going to talk about. Attached to this list were two pages on which she wrote answers to these questions. “The answers on the next two pages are excellent,” she wrote at the end of the document. She had never mentioned these answers to me. They probably date from the final years of her life, at a time when she was starting to feel a certain pessimism. I decided to add these answers to the end of the original interview, like an addendum or an anti-conversation.

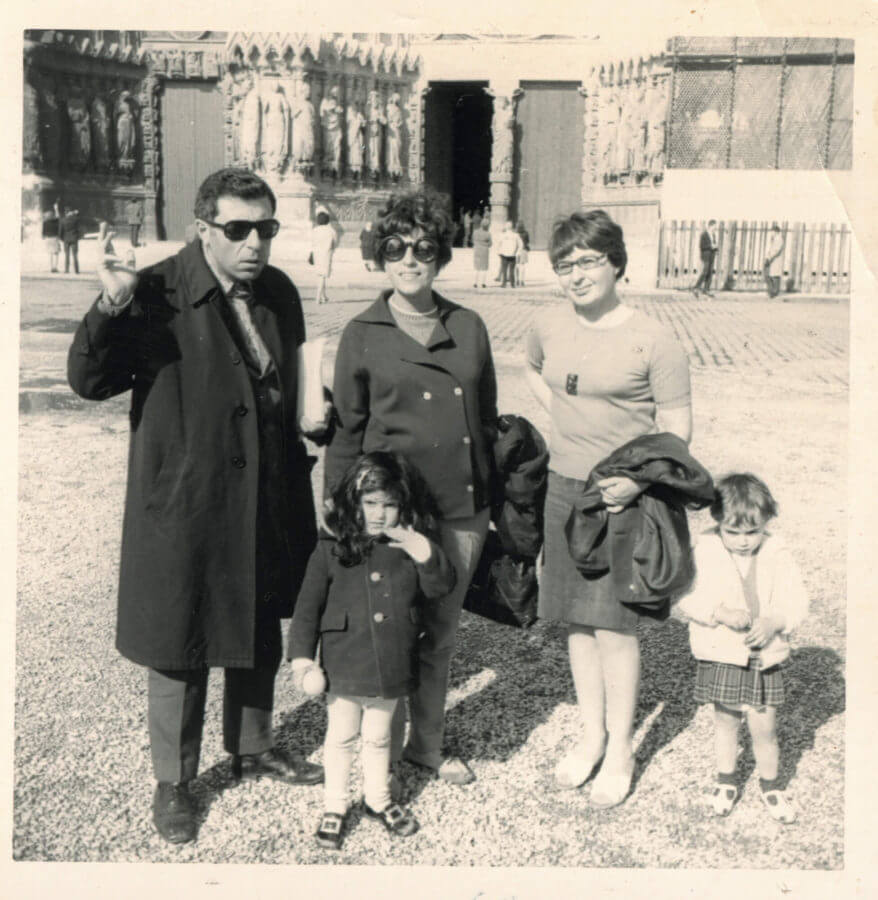

N.S.: We are meeting today to start a conversation about your background, your works, and your thoughts… A long, productive career such as yours means there are a lot of questions to address. You started working as a professional artist right after you graduated from the Fine Arts faculty at the University of Tehran in 1954. In 1955, you left for Italy before coming back to Iran in 1959. In 1980, you settled permanently in Paris. You travelled a lot, your work has been shown in numerous exhibitions, and you have remained active up to this day.

Let’s start with your beginnings, when you were about to leave for Italy. You were in your thirties and were already an active artist in Iran.

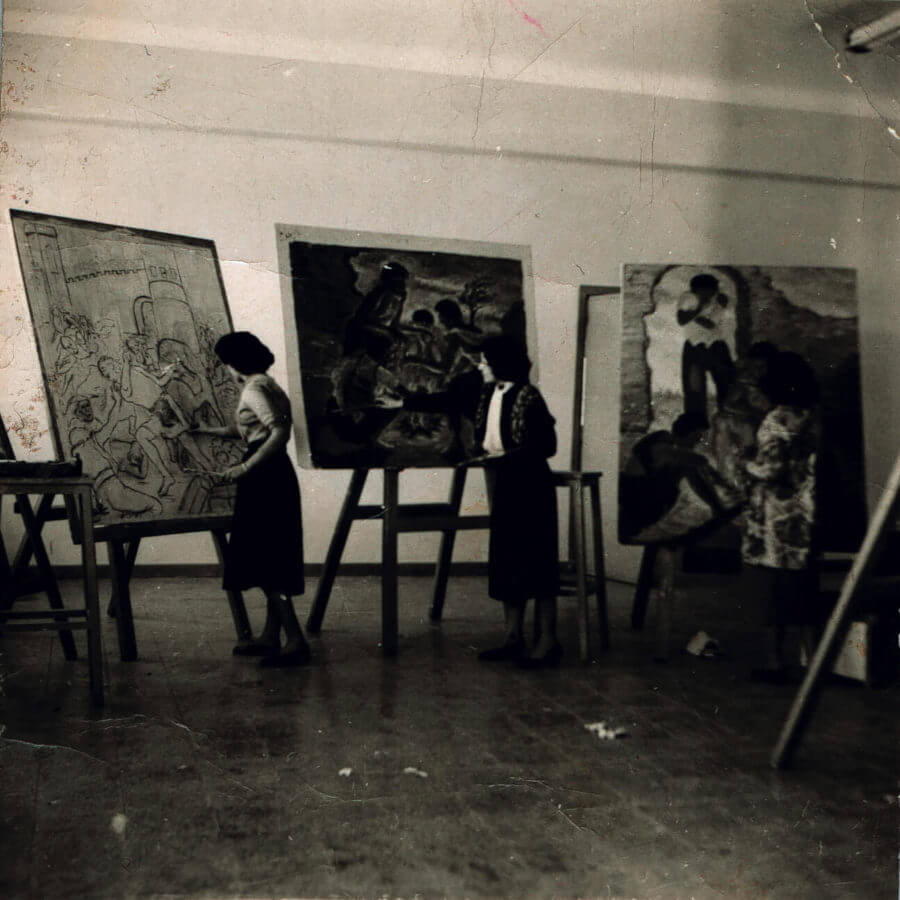

B.S.: At that time, I had a thirst for learning, I was extremely curious and I seized every opportunity to discover and learn. I’ve always been a non-conformist, a rebel hiding under a quiet and docile appearance; my true nature is completely hidden. With a couple of friends from university, such as Sohrab Sepehri and Nasser Assar, we formed a group of young artists and tried to keep up to date with artistic events worldwide and to carry out our experiments beyond the academic curriculum. Unfortunately, our means were extremely limited, and our research sources rarely went beyond the books we found at the university library.

I believe cultural exchanges with the West were very limited at the time.

Very much so… During this period, I was also involved with another group that wasn’t connected to the university. They were intellectuals and artists, most of whom had lived in France and were strongly influenced by French culture. They were mostly talking about poetry and literature, Baudelaire, Éluard… This is where I met the poet and filmmaker Fereydoun Rahnama; we remained friends until he passed away in 1975. Iran has an old poetic tradition, so we could debate and exchange views on subtler issues in that field. It seemed there was something missing in the field of the visual arts. Everything was more reserved, more restrained. Belonging to this group and taking part in their conversations on French literature strongly encouraged me to discover the Western world.

Despite the scarcity of exchanges with Europe at that time, a number of painters were already attempting to explore European art, following the path laid down by Kamol-ol-Molk. However, this type of approach didn’t really interest you…

There were two groups of artists that followed quite distinct currents. One group followed the teachings of Kamal-ol-Molk,1 and its works more or less influenced by their master’s style, inspired by classical European painting. The other group was made up of artists who had studied in Europe; they were labelled modernists, and yet their style was closer to late 19th, early 20th century European painting.

How was your own painting characterised in this context?

I mainly worked with dark colours. Later, I focused on stylising forms while simultaneously introducing brighter colours. Representing reality has never been important to me. Reality was just a pretext for creating forms and colours. This trend had nothing to do with the influence of the teachings at the Fine Arts faculty when I studied there. I would say it had been deeply rooted inside me for a very long time. Before going to university, I spent some time taking painting lessons with one of Kamal-ol-Molk’s students. He gave traditional, academic lessons. One day, in his class, I chose to paint a fan instead of doing a figure painting or a traditional still life of a series of objects on a tray. It was unusual. This object was lying in one corner of the room, unnoticed by anyone. The mechanical components and the blades allowed me to play with lines as I pleased. From that moment on, this sort of play became more important to me than representing reality. Later on, with my movement-based works, I linked this interest in fans to the movement of the blades. I sometimes reflect on this choice, and with hindsight, I can see the origins of many later choices I made.

Once you arrived in Italy in 1955, you must have found a more open field to delve into what initially pushed you to draw a fan.

I feel very lucky to have been in Italy at that period. I first went to the Rome Academy of Fine Arts, then to the Napoli Academy. In Rome, I worked in Roberto Melli’s classes, which welcomed young international artists with a scholarship. I only stayed there for a couple of months. As always, I needed to lead an active life, and I needed things to move around me. I wasn’t satisfied with these classes. Around this time, a simple incident completely transformed my approach as a painter. One night, as I entered my room, a long string I was holding in my hand fell on the mosaic floor at the entrance. It created tangled lines with expressive curves. There was something fascinating about it. I repeated the same gesture several times, dropping the string repeatedly, and each times it created different shapes. After I had this experience, I knew I was going to work differently. One day, I decided to start working at home. I abandoned the materials and tools we used at the Academy and launched into my own personal experiments. I replaced my paint tubes with large paint containers used in the construction industry. I also bought large palette knives and scrapers. I would spread my canvases on the floor. This was when I stopped using an easel. I would work day and night, relentlessly. After a six-month absence from my painting class, I ran into Roberto Melli. He asked to see my works. His reaction to these new paintings filling my room was more than encouraging. He advised me to take this approach further and gave me the scholarship money the Academy had received during my absence, telling me to buy more paint and painting material with it.

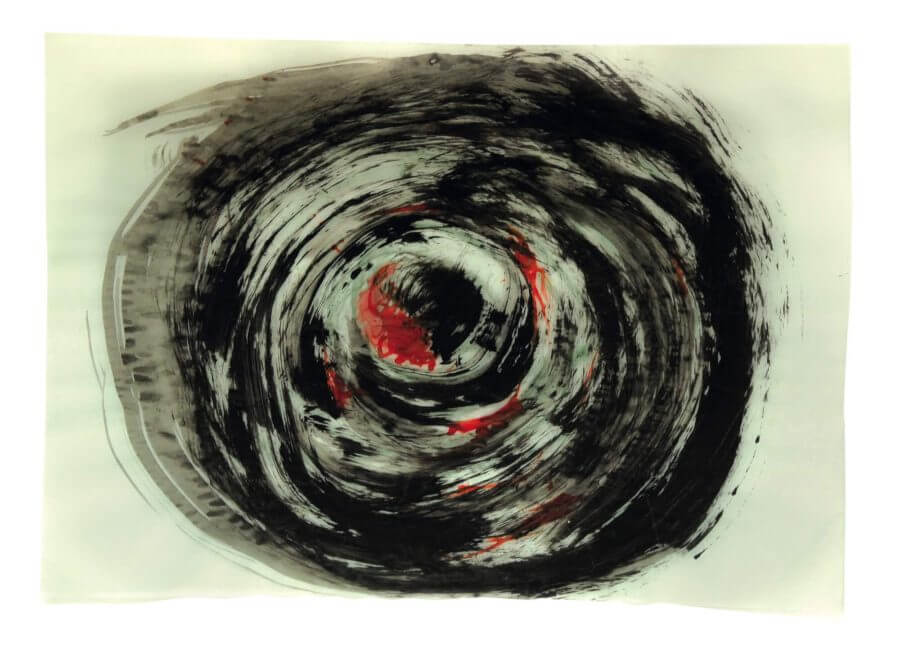

This key moment in your life as an artist, around late 1956 and 1957, became a crucial period in Iranian modern art, too. You pioneered the move towards abstraction. Could you speak more about the new way of painting you were developing at the time? You first mentioned an incident that triggered your experiments, yet there must have been deeper reasons. What made you give up the easel and figurative painting at once?

I cannot tell you the exact reason, but I felt an uncontrollable urge to put my canvases on the floor. It allowed me to make much larger moves, and offered me a greater control over my gestures. The relation between my body movements and the forms they produced fascinated me. I was interested in every aspect pertaining to the act of painting, even when I accidentally dropped cans of paint on the canvas. Each time, it created a random effect I had to carefully control. In the first series, the lines are not as large, and the expression relies much more on colour. But a couple of years later, in the early 1960s, I greatly developed the gestural dimension in my approach.

In the first series you mention, one notices links with informal or lyrical abstraction, a current that started in France in the 1940s, a time when avant-garde painters were also undertaking various experiments in corporeal gestures and movements; these experiments compelled artists to lay their canvases on the floor. I am especially referring to Pollock’s “dripping” technique from 1946 and the works Alechinsky made upon coming back from Japan.

These trends did exist, but as you know, the artists experimenting in that way used so many different practices. Pollock’s method was to drop paint onto the canvas. Alechinsky was influenced by Far-Eastern calligraphers. In my work, I would first drop paint onto the canvas, before spreading it and arranging it. Concerning informal abstraction, one could say that all forms of non-geometrical abstraction were somehow related to that movement, as is shown by L’Art abstrait, a four-volume book published in 1974.2 One should remember that this was a very vague classification. In this book, Michel Ragon introduces me as a non-geometrical abstract artist, which seems logical to me. However, I never had a close relationship with informal abstraction and the artists linked to this current.

These practices did produce extremely diverse effects and expressions.

The possibilities were quite vast. I worked in a kind of ecstatic mood born of my intuitions. I constantly questioned myself, and my work was also an attempt at seizing or recovering real emotions. In order to reach this goal, I would play with paint and colours, with canvases, and with tools. I took great enjoyment in these practices. When the compositions resulting from these games conveyed strong emotions or evoked a significant moment, I knew the painting was complete – which was not always the case. As you can imagine, these approaches were far from being aimless. My primary goal was indeed to reach an equilibrium between colours, composition and matter. Capturing fleeting moments was already a crucial concern of mine at that time.

What kind of capturing are you referring to?

I’m able to memorise in detail a momentary shift in light. Sometimes these occurrences become significant moments that inspire my work. However, I never reproduce them as they are. I’m more inclined to look for a parallel expression that allows me to convey these moments without reproducing their original surroundings.

This relationship with nature or with reality is interesting. You don’t produce environments, events, or any existing object, but you invent forms and expressions able to make the audience experience what you have seen or felt in front of reality.

Indeed, this could be a fair description. I’m inspired by nature and by everything that surrounds me, but I don’t paint it directly. It’s their effect I’m trying to reproduce.

Let’s also talk about the way you present your work. Your paintings are made on open scrolls, laid out on the floor, and can rarely be displayed as they are. Choosing the way to present them thus becomes a significant defining gesture.

I used to choose the areas that interested me on the open scroll before cutting them in order to fit them on a frame.

This method allowed you to get rid of the easel, but also to set yourself free from the pre-established frame of your flat surface. The frame becomes a subsequent addition to the work, similar to a late compositional element. Choosing this frame is therefore a creative stage in itself…

Indeed. Unfortunately, many works from this period that were not fixed on frames have disappeared.

After years of academic work, this series of paintings allowed you to discover a highly personal style and identity.

I felt I had freed myself from my chains…

Let us also mention the reception of these works in Italy. Your first one-woman exhibition in Rome took place at the Il Pincio gallery in 1957. This was your first real step into the professional art world.

I was invited to the Venice Biennale in 1956, but it was a rather subdued presentation: I exhibited a still life. There was no Iranian pavilion at the time, and the Italian pavilion proposed a space to display the works of a few Iranian painters, among whom Marco Grigorian and I.

Il Pincio was not a major gallery, but it was extremely well located: many people from the Roman intellectual and artistic scene frequented Piazza del Popolo. Fellini was among the first people to visit the exhibition and to take an interest in my work. Lionello Venturi also discovered my work in this gallery, and subsequently introduced me to the La Bussola for another individual show.

This was a very renowned gallery.

I did an exhibition there in 1958, after Hans Richter. La Bussola usually exhibited well-known artists. But it also supported a highly limited number of young artists. For this exhibition, I even had the luxury of having an illustrated brochure with a preface by Emilio Villa. He was impressively cultured. He was a philosopher, a linguist, an art theorist, and a great connoisseur of Eastern culture. He references Zoroastrian texts in his preface.

What was the critical reception to your work?

Very positive. The Appia review mentioned the exhibition in an article by Emilio Villa highlighting my work. I was so immersed in my experiments that I didn’t care whether the critical reaction was positive or negative.

With hindsight, the radical stylistic change you took so early after your arrival in Italy seems quite extraordinary.

Today, nearly fifty years later, I still wonder about this change.

Don’t you think encountering the rich and vibrant Italian artistic culture may have contributed to such a renewal?

It must have played a part. I was fascinated by the artistic atmosphere in Italy, but also by Italian culture in a very broad sense: the streets, the people, the whole city of Rome…

In Italy, I discovered Italian culture but other cultures as well, both Western and Eastern, from every historical period. These discoveries were made possible through large, thematic exhibitions organised in many of the country’s museums. I learned a lot, even about my own culture – Iranian culture – thanks to these exhibitions.

In 1959, nearly two years after your exhibition at La Bussola, you went back to Iran. After travelling back and forth between Iran and Rome until 1961, you settled permanently in Tehran, even though everything seemed possible for you in Italy. In 1960, one of your works appeared on the cover of the 27th issue of Aujourd’hui. Was it the right choice to leave Italy at that time?

My scholarship was coming to an end, and I had to get back home. I didn’t intend to abandon my work. I brought most of my canvases back to Iran. I was given a professor’s position at the Fine Arts faculty at the University of Tehran, which allowed me to resume my activities in my country.

Could you keep on working the same way as you were in Italy?

My position at the university prevented me from focusing entirely on painting, but with perseverance, I managed to work and produce extensively.

You took part in a lot of exhibitions after that return, both in Iran and abroad, in individual and collective shows, as well as in several major biennales. In 1962, at the Venice Biennale and at the Third Tehran Biennale, you were awarded the first prize; in 1963, you went to the São Paulo Biennale. In 1963, you also took part in the exhibition Comparaisons at the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris. Those were rather fruitful years. These were periods of intense activity. How did it affect your work?

It developed progressively, through several changes occurring in my work. During the Italian period that you linked to “informal abstraction,” I used scrapers to spread and arrange the paint on the canvas. This approach often produced thick layers of colours. I progressively started to develop the act of spreading the paint, up to removing colours with my scraper. I would pour colours on the canvas, then remove them afterwards, in order to create shapes. I started appreciating a kind of “negative” painting. More generally, I turned towards thinner materials. I had experimented with this method only once in Italy, for a work that was exhibited at La Bussola. When he visited the exhibition, art critic Julio Argan noticed it and advised me to delve further into this approach.

This method created more pronounced forms and signs, while somewhat downplaying the importance of colours. By repeatedly removing colours, you seem to have acquired an impressive control of your gestures, which built the architecture of your works. Your productions from this period demanded a lot of strength and physical ability, as well as a lot of maturity in order to harmonise all the movements and to control the composition, while acting very quickly on flat, often very large surfaces.

These works had to be done in one go. You had to get it right from the start. Any correction would weaken the signs and the movements.

There were also new choices in terms of colour. In the paintings of this period, we note an inclination towards blue and green…

In 1962, I was commissioned to do two large, 90 square-metre ceramic mural boards for the façade of the Hilton hotel in Tehran. This work led to long research and investigation into traditional Iranian ceramic forms and techniques. I think these studies further attuned me to the dominant use of blue and green in these ceramics. So these boards were an interesting occasion to focus on traditional Iranian art.

Are there other traces of these investigations in your work?

I don’t think so.

As you mentioned traditional art, do you think that your work generally has something of traditional Iranian art and culture to it?

I think every artist is influenced by the surrounding society, culture and environment. The 20th century offers many ways to communicate, to travel, and to exchange. Not only are we influenced by our traditional cultures, but also by our entire multicultural, global environment. I’ve been influenced by everything that caught my attention without caring for its origins. Besides, I’ve always felt a kind of anxiety that seemed to pervade everything. This feeling is difficult to express. I see it as an anxiety linked to our era, and which seems to leave its mark everywhere.

You have travelled extensively. You are consequently infused with different cultures. Was a cultural enrichment, in a larger sense, the only thing to come out of these journeys?

I don’t think so. Travel often provides privileged moments for reflection and emotion. It leads to persistent visual memories. I still remember images from trips I took when I was a child. Childhood discoveries are powerful events, and they always stay with you. I will never forget some scenes I witnessed as our family travelled to the countryside, like the sight of tree plantations. I ran among these plantations, and the vertical lines of the trunks pierced through my eyes with a fascinating rhythm. When I ran, bands of crows flew away, and their chaotic, brisk movements impressed me. Sometimes I think that this memorable experience already explains a great deal of my subsequent pictorial experiments. On the road going through the Alborz mountain range, I was fascinated by a passage at the heart of those black, rocky mountains. We were driving between these huge walls of stone. I was in awe of their power. I keep a lot of similar images in my mind, coming from different places. They are still with me, and they certainly inspired my work.

Surprisingly, in 1967, you launched yourself into a kinetic period.

It all started with an art competition organised by the Unesco for a campaign to fight illiteracy. I produced a work with black blinds covering a canvas representing the sun. When you opened the blinds, the sun would appear.

You won the first prize with this.

Afterwards, I kept on working with blinds, and I had the idea of using engines to open and shut them automatically. I carried out rather interesting, unusual and diverse experiments with blinds. I made installations that also played with light refracted on concave mirrors. For some of these, I stuck aluminium foil on one of the faces of the slats in order to create reflections of broken lights.

How did people react to these installations?

Very negatively. Both the Iranian audience and critics completely rejected these works. One of the most renowned critics of the time even wrote a very offensive piece about them. I didn’t sell a single work from this series.

And yet, as usual, you didn’t seem to ascribe importance to those reactions…

I took a sabbatical year in Paris around that time.

You must have felt some satisfaction when you found out that avant-garde, kinetic works where exhibited in famous Parisian museums and galleries…

I also felt sad.

The period you chose to come to Paris (1967–1968) had been the most agitated since the Second World War. France was in turmoil. How did you experience this?

I had never been interested in politics. But this doesn’t mean I didn’t have a political understanding or maturity. I was still very individualistic, and the idea of acting under the banner of an imposed ideology was completely unacceptable to me. In the midst of the riots, I kept on working. I would visit galleries and carry on my investigations. I worked with Gustave Singier, a teacher at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Above all, I wanted to develop an art pedagogy method. Researching that was quite interesting. Among other things, the relation between students and teachers fascinated me. The latter were extremely attentive towards their students. I was impressed. Maybe that was because we were in a rather unique historical moment.

Did this experience with art pedagogy allow you to improve teaching methods at the Fine Arts faculty at the University of Tehran?

Despite my efforts in that field, I was confronted with a certain opposition. Much later, though, when I became director of the Visual Arts department, I managed to carry out a number of my pedagogical projects.

You took another sabbatical year and went back to France in 1974–1975. Paris was quieter in socio-political terms. In contrast, the art scene was very dynamic at that time, both in quality and in quantity. These were indisputably significant years for you.

My sojourn was spent in the best conditions possible. I had a workspace at the Cité des arts and I worked very intensely. There were numerous art events, showcasing various currents, and I tried not to miss any of them, whether they were major or more marginal events. I wanted to discover everything without any preconceived judgment.

In the meantime, you stayed true to yourself.

I kept on experimenting serenely.

Your works from this period were exhibited in Paris, in two one-woman exhibitions. One of them took place at the Cyrus gallery, and was presented by Michel Tapié.

It was important to show these works in the city they had been conceived and created.

Listening to you, one gets the feeling that going along with your time was one of your major concerns.

Absolutely. I think it is essential for an artist to be contemporaneous to the world that surrounds him or her.

This dynamic, artistic life that surrounded you, as well as your persistence in your experiments, seem to have led you towards more experimental approaches that were later asserted in Iran.

Throughout this period, the experimental aspect of my approach was indeed more visible, but it had always been the case. I’ve never settled for reproducing variations of one single successful style. I was attracted to the moment of experimentation and of discovery.

During this period, we notice several types of experimentation conducted simultaneously in different styles.

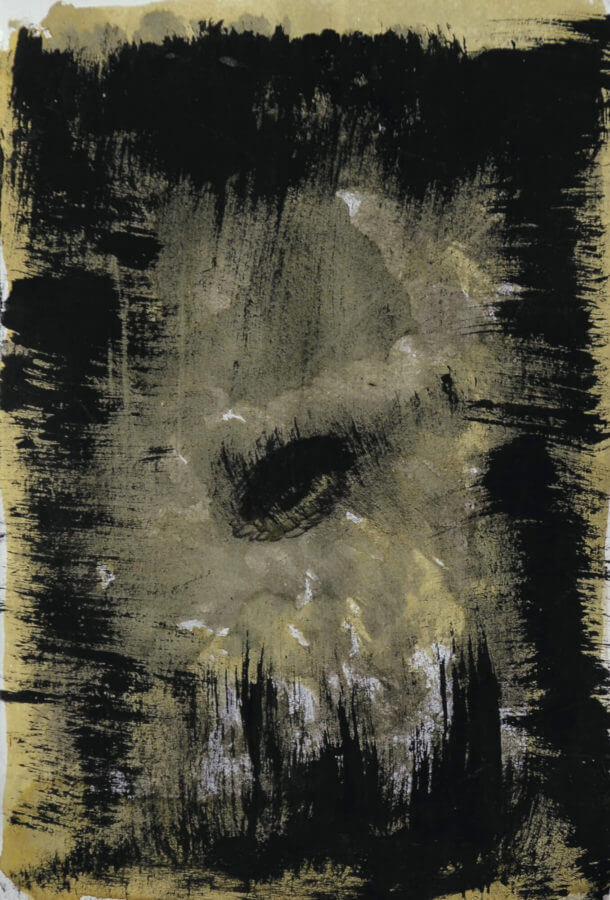

In one series, I would go towards sculptural forms. By introducing a void around voluminous signs, I created silhouettes of more or less sculptural objects. This type of disposition gave the sign an imposing appearance. The concern of respecting the void around the painted volumes somewhat modified my approach compared to what I did in the past. I had to follow a more careful, calculated process.

In another series, you were experimenting and playing with lines… There were multiple lines that repeated themselves, creating rhythms. In some cases, these lines were overlapping or crossing themselves, creating intermingled shapes.

All things considered, this approach was not so different from a number of works I did in Iran before, but the fact that I used a tool gave them a quite different quality. I had this one tool, which initially I didn’t know how to use. It was a dented instrument that left parallel traces on my supports, similar to hatchings.

Speaking of supports, you also tried new materials in that domain.

I tried using aluminium; this support suited my way of painting. It was a smooth surface for using my tools on. I also liked its silver-grey colour. Later on, I used aluminium foil glued on hardboard backing.

During this period, and in this series in particular, black became a very dominant colour.

I have always loved black. In 1955, during my first visit to Paris, the lights in this city fascinated me. In Iran and Italy, shadows were much softer, the colours paler. In Paris I was extremely influenced by the dark, almost black tones of the trees lining the banks of the Seine in winter. I’ve always found black to have a great intensity and a great expressiveness. Day after day, I found more power in this colour, and I wanted to work exclusively with it. Other colours appeared in lighter touches, episodically, but I found this enough.

In this series, the presence of lines, the underlined rhythms as well as the dominant black inclined you towards a certain idea of writing and of calligraphy.

Even though I knew Persian writing and calligraphy well, I never tried to go in that direction.

I was not referring to writing and calligraphy in the traditional sense, but more to plastic and gestural relations, the link between your gestures and a calligrapher’s, for instance.

Applying the scraper to the support is indeed quite similar to the gesture of the calligrapher working with a kaalam.3 There is also a link between the colour black and the calligrapher’s ink.

Outside of these works and the ones in which scriptural signs emerged, you developed a third form of expression during your 1974–1975 Parisian sojourn…

They were works with broken rhythm. I always act in reaction to my own works. The presence of signs and of large lines gave me the desire to elaborate a series of works based on small, repetitive movements, by opposition. The usual large signs and powerful lines gave way to more nuanced and rhythmic hatchings.

In one of the later works in this style, you also broke down the single frame, replacing it with a multitude of juxtaposed frames.

These date back to 1977. Nine small, square canvases were juxtaposed in order to create a single work. Each canvas represents a rhythm. They were inspired by a brick ceiling I saw on the vault of the Jom’eh (Friday) mosque (Masjed-e-Jom’eh) in Isfahan. I realised the vault’s concave ceiling was built with a large number of square elements. Each of these was covered with rhythmically set bricks. What caught my eye was that each element had a different rhythm, but the disposition as a whole conveyed the idea of a global order. I was strongly impressed by the ingenuity of this technique.

The presence of rhythms in this series and the ones with calligraphic lines brings about a kind visual musicality. Were you seeking to express yourself musically?

I never was.

Did you like to accompany your gestures with music when you worked? A number of gestural artists like to immerse themselves in music while working. For Hans Hartung, for instance, music while working played a crucial creative role.

I need silence when I’m working. I need to hear the sound of my scraper as I move it on the canvas. This is my favourite musical accompaniment.

In 1980, you settled permanently in France.

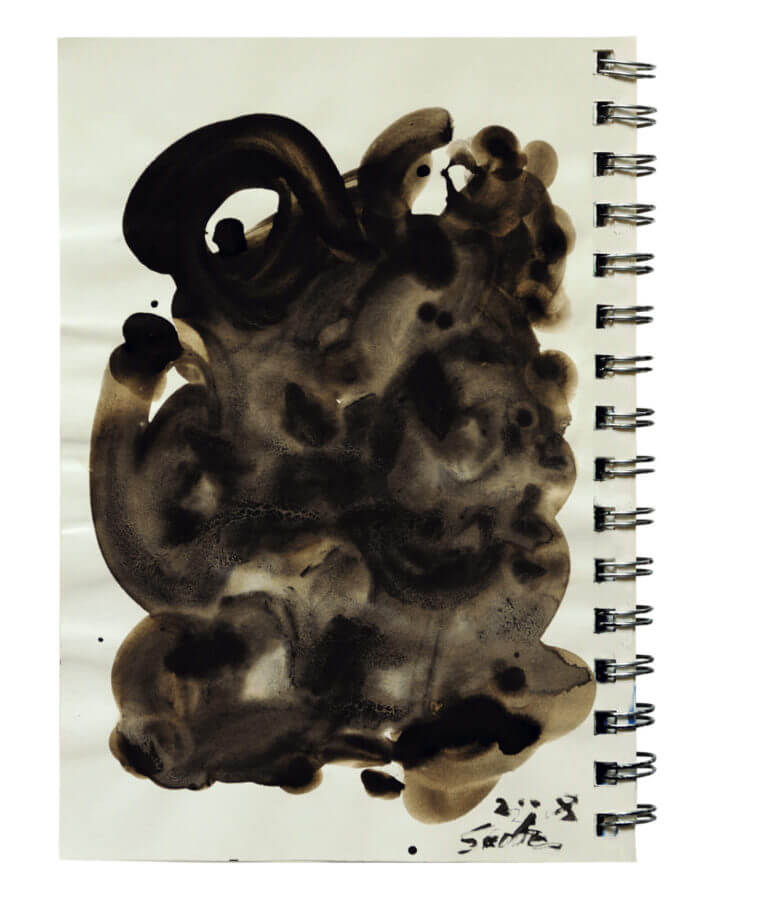

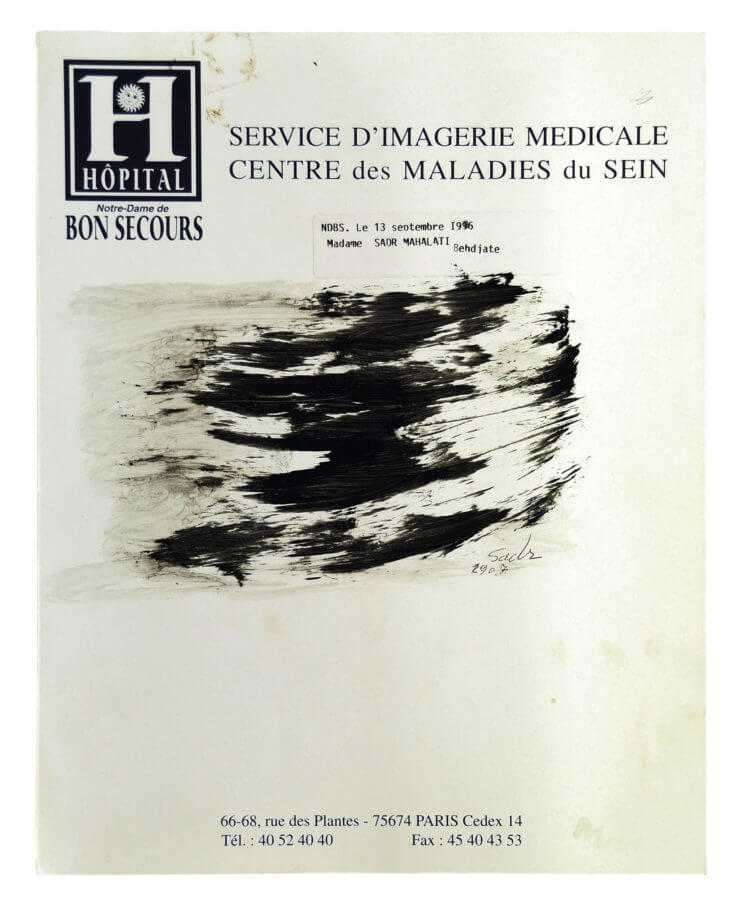

When I came back to France that year, I didn’t have settling down in mind. Initially, I had come to travel with my daughter, who was continuing her studies in France. This was during the Iran-Iraq war, and airports were suddenly closed down for a while. While I was waiting for a chance to return, I was diagnosed with cancer. It was 1981. So I decided to stay in France to get treatment. That was the beginning of a long string of successive illnesses. As soon as I was cured, I was diagnosed with another cancer in 1983. These years saw me spend most of my time at the hospital. Even when I was outside, the shadow of the illness was hovering everywhere.

These illnesses and these hospitalisations must have prevented you from working…

Not quite! I would keep on working as soon as I got the chance. I even worked and did exhibitions during a period of chemotherapy. It was an individual exhibition at the Darial gallery in Paris, presented by Pierre Restany. When I learned this exhibition was being organised, I forgot my physical state and I focused on creating new works! In such situations, you can’t be sure about anything about your future; your artistic activity takes on another meaning. It’s hard to describe. Strangely enough, art becomes something very serious, something to cling to.

How did you manage to combine your illness and your work?

During this period, I turned to new working materials. I used less physically demanding techniques. This is how I launched into a long period of photomontages and photo-paintings. These techniques allowed me to use countless pictures I had taken. I’ve always taken a lot of photographs, and I still do.

So you turned to these techniques only because of your illness…

Partly so. Necessity does play an important role when it comes to making a choice. In this particular case, I need to mention I had made a photo-painting self-portrait in 1965, in which I also included writing. This work had been widely criticised in Iran, which dissuaded me from continuing down that road.

What were you looking for with these new series?

I was looking for something new. In my 1981 exhibition at the Cité des arts, I had only shown photomontages. Painting collages had yet to appear. I wanted to extend the field of my experimentations, and this is how I returned to photo-paintings. These works were exhibited in 1984. I would create compositions with cuttings from photographs and paintings. This technique was quite close to what I was doing before. The paint in the first photo-paintings was entirely made with a scraper. In subsequent works, I used other means, coloured pencils among them.

Writing about these works in his preface to your 1984 exhibition, Pierre Restany highlights very clearly the trace of your memory on your current references: “[…] This flashback is accepted by the eyes of the painter, as far as the threshold of accuracy, which means that the truth of memory is left exposed. Thick, parallel hatches of black paint frame the central photograph, the heart of the message, the essence of the vision. Through this focalising window […] Behjat Sadr objectivises the fragment of the past she examines with the serene precision of a laser or a surgical scalpel. The operation is perfectly developed: the effect is equally striking when the artist applies it to references to the more immediate space and time of her existential consciousness, the banks of the Seine, for instance.”

This text provides an admirable description of the nature of these works. The relation between past and present was essential in this series.

I like this text.

After so many years of remaining faithful to abstract art, these works have a narrative aspect that stems from the presence of photographs.

My abstract works were always moving to and fro between the inside and the outside, the subjective and the objective. Besides, capturing moments had been an important thing for me for a long time. The reason I was interested in photography was also, right from the beginning, this capacity of seizing fleeting moments. In my paintings, the expression of moments would appear in an abstract form; in my photomontages, I would arrange photographs and painting cuttings so that that there was no real disposition. It was a way of playing with “true” and “false” by reconciling these two notions.

Despite everything you say, you could cut the photographs so that their narrative aspect disappears, yet, you still wanted to retain a narrative aspect.

In some of my works, I did precisely what you are saying. For instance, I cut pictures of tree trunks in very small pieces and used them solely to create rhythmic patterns. Besides, using pictures gave me the idea of replacing them by coloured, cut strips in several works.

I mentioned your coming back to narration through your photo-paintings because many abstract artists have done so later in their lives, during more mature periods. I thought that this type of return was maybe necessary in order to establish a new relationship with nature and the real world.

I didn’t feel such a need to return to narration. All along my career, the most important element, the one leading me towards new directions, was chance. Any change of style in my work has been a consequence of chance.

Chance certainly produces many significant things, but choosing a particular practice in opposition to others may be a sign of an unconscious inclination towards it.

Probably. One should not forget that I created these photo-paintings during periods of illness. In such a situation, the very act of cutting and pasting was an important activity with significant meaning. While I was working, I thought that these image cuttings belonged to different periods, and that the act of rearranging them into a single work was echoing my own life. I saw life as a sort of collage at the time. Right now, I have stopped making such works, I’m following a different process, but I’m surprised to realise that I keep on making collages with sequences of my life stored in my memory. Maybe this idea has deeper roots inside of me.

After this period, you replaced pictorial practice with writing…

Not exactly. I’ve written in parallel to my visual practice for years. My more recent works use a wide array of techniques. Right now, I like to write more. I write about many things, about paintings, about my thoughts or my observations at various given moments. I frequently call forth my memory. Like my paintings, these writings are a part of me. It seems to me that the desire to paint and the desire to write stem from the same source, from the same need to express oneself. These practices complete each other, and replace each other if necessary. This work on memory has led me to a new phase, where many things that make up my life today catch my attention. I’ve had two retrospective exhibitions, one in Paris in 1990 and another in Iran in 1995, which was meant to introduce my work to the younger generation. These retrospective shows have had significant consequences for me, insofar as they provoked a journey towards my past that provided me with a renewed self-knowledge. In turn, this knowledge gave a different meaning to my everyday life. Today, I fully enjoy my everyday life, without setting an agenda for the future. I bring my silence and my past into noisy cafés, I observe everything around me and write. I enjoy being interested in many small things. Our conversation today belongs to this process.

Don’t you see yourself publishing your writings? They could cast a considerable light on your paintings for your current audience, and for those who will study them in the future.

I’m contemplating a probable publication. But this requires a lot of organisation.

During the course of our conversations, we highlighted various aspects of your practice. Among your different artistic attempts, what do you think will be remembered as your most significant contribution?

I don’t think about the future of my work. The future will decide.

Is posterity unimportant to you?

It was when I was 30. When I visited the Louvre for the first time and saw the Mona Lisa, I told myself that Leonardo da Vinci was not there anymore, and that everything was over for him; the endless queues of tourists in front of his painting didn’t matter.

Today, I’m 76, and I realise I feel the same as when I was 30. I would even say that I’m even more convinced of it now than I was then.