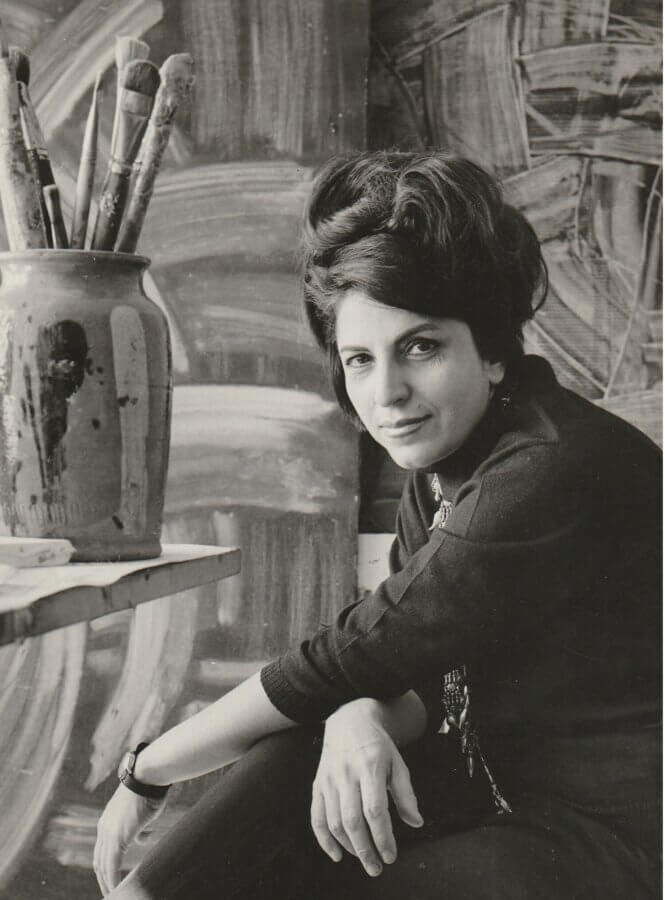

Behjat Sadr; 1924, Iran-2009, France | A Commemoration

par Leili Adibfar

May 29, 2024, marks the one-hundredth birth anniversary of Behjat Sadr, the pioneering Iranian artist! Born in Arak, Iran, Sadr grew up in a household open to the world and simultaneously observant of Iranian rituals and traditions. Due to her father’s career as a government employee, Sadr’s childhood was spent moving from one region to another—from “central Iran and [its] deserts to the north and [its] green, orange, and red trees.”[1] Sadr completed her primary and secondary studies in Tehran, where her family eventually settled. She came of age as the Allies invaded the country in the summer of 1941, a period she recalls in her journals as a chaotic year. Despite the turmoil caused by the invasion, and encouraged by her mother, Sadr pursued a career in teaching and became a secondary school teacher in 1943.

In 1948, Sadr enrolled in the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Tehran to study painting. Her graduation in 1954 coincided with the aftermath of the 1953 Iranian coup d’état, which overthrew the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh and enhanced monarchical rule. The coup, which occurred shortly after Mosaddegh had led a movement to nationalize the Iranian oil industry, undermined the expected path to democracy and ushered in an era of national despair. Obtaining a scholarship to Italy, Sadr left Tehran for Rome in 1955 to continue her art studies. In 1959, she returned to Iran as an associate professor in the Faculty of Fine Arts, working for the next twenty years as an artist and educator. After living through the events of the Iranian Revolution, Sadr left Iran for France in 1979, where she continued her art practice and died in 2009.

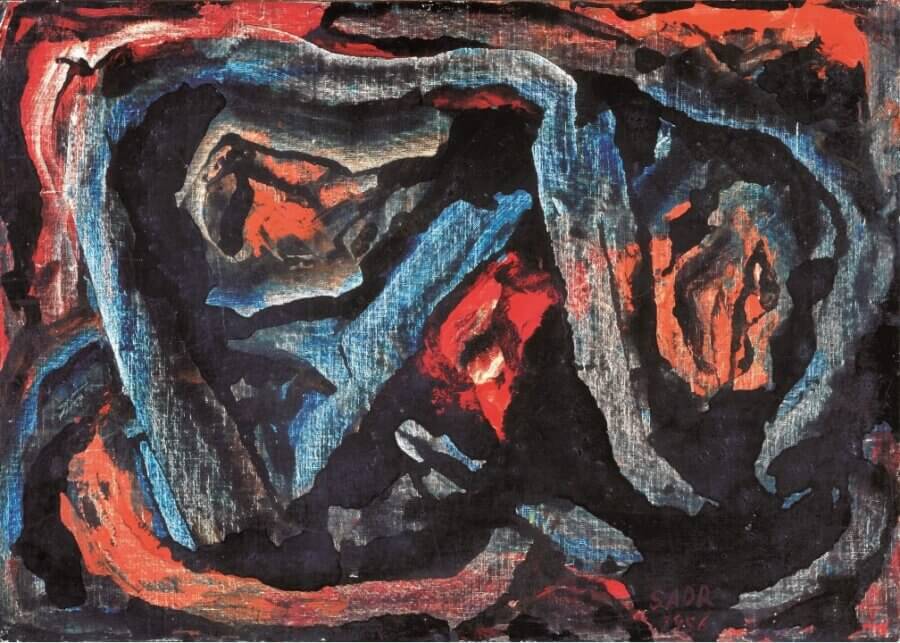

Sadr’s fascination with the formal and material components of the appearing world redefined her stance toward reality and the modes and manners of its representation from the early stages of her practice. “Representing reality,” she once said, “has never been important to me. Reality was just a pretext for creating forms and colours. This…had been deeply rooted inside me for a very long time.”[2] In pursuit of her phenomenological engagement with the concrete world—and encouraged by postwar art practices and discourses—Sadr abandoned easel painting and spread her canvases on the floor shortly after arriving in Italy. She also began to use palette knives and industrial paint. Seated and moving her upper body freely above the canvas, Sadr would pour paint onto the canvas and continue to shape and remove it, pushing the pictorial space of painting closer to the dynamic arena of the world. Her paintings from this period depict expressive swirling strokes that are improvised yet structured toward the construction of a cohesive composition.

Sadr’s return to Iran coincided with the onset of a pivotal era—the eventful 1960s—marked by the consolidation of a nationalist discourse under royal power. Fueled by rising oil prices and driven by the notion of progress, the Shah implemented rapid modernization efforts across Iran, notably through the White Revolution of 1963, with granting women the right to vote and land reform among its key programs. The oil-fueled modernization transformed the economic, social, and cultural landscapes of the country and fostered the expansion of a substantial urban middle class. However, the strategies and approaches to its implementation, along with the struggle to reconcile the inherent contradictions between monarchical rule and democratic principles, gradually caused socio-economic tension and political unrest.

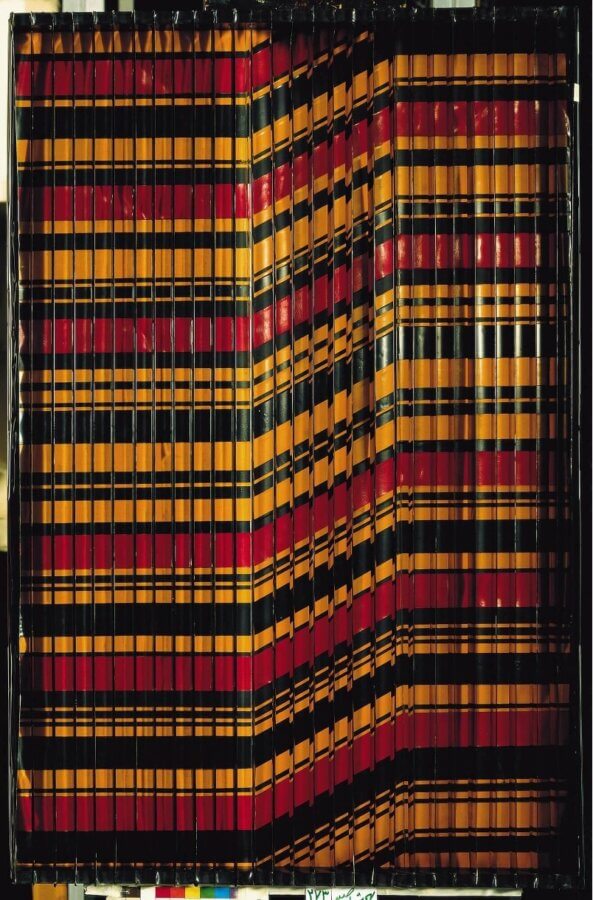

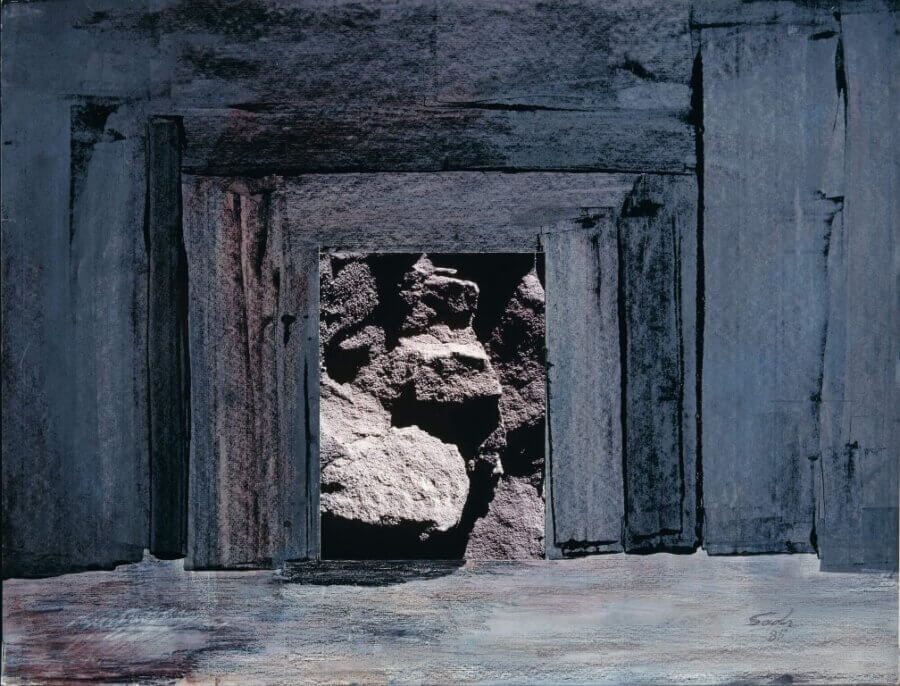

The 1960s was a prolific decade for Sadr. Based in Iran, she regularly participated in national and international biennials and exhibitions. Maintaining a critical distance from art practices that sought to respond to the formation of a national identity, she continued to favor a phenomenological approach over the application of vernacular iconography common at the time. In the first half of the decade, Sadr pursued action painting with a sustained aspiration to remove paint from the canvas and form strips out of negative spaces. Aligned with the rising pace and movement of modernization, she began making kinetic works in the later years of the decade, which were variations of abstract canvases under moving or fixed Venetian blinds. By the 1970s, Sadr’s work had mostly evolved into rhythmic yet disenchanted patterns on various surfaces, including aluminum, at times suggesting a viscous imagery of oil as the substance of modernity. Her unique approach visualized the dark chaos of extractive modernization and questioned the promises it could offer to Iranians at midcentury. Later in her career, as illness began to affect her body and exile shifted her perspective, Sadr transitioned from predominantly working on large-scale paintings to creating smaller photomontages in the 1980s. Despite these changes, Sadr’s profound appreciation for painting as a means of personal expression remained at the core of her practice. Notably, her collages integrate her distinctive mark-making as internal components or within the framing boundaries of the works.

Over five decades of artistic practice, Sadr’s relation with nature—red, blue, green, and bleak nature, rendered and altered nature—threaded through various phases of her work, echoing her personal transformations during different stages of change in modern Iran and beyond. To Sadr, however, nature was not merely an isolated subject for representation; it was a realm to be experienced and perceived by the artist. This fascination with the substance of the world found expression in Sadr’s art amidst the weight and challenges of war, revolution, and migration. With black paint poured onto surfaces and knives and blades smeared in paint, Sadr made horizontal and vertical strokes in harmony with her body and awaited the slow drying of the created forms with elation: “I don’t always need light. The darkness of the dark is quite alluring, too.”[3]

**

Leili Adibfar studies art history at the University of Illinois at Chicago and is currently completing her dissertation, a monograph on Behjat Sadr.

1 Behjat Sadr’s notes, n.d.

2 Behjat Sadr in conversation with Narmine Sadeg, “Conversations with Behdjat Sadr, followed by an ‘anti-conversation,’” in Behdjat Sadr: Traces, edited by Morad Montazami & Narmine Sadeg (Paris: Zamân Books, 2014), 203.

3 Behjat Sadr describing her work process in Behjat Sadr: Time Suspended, directed by Mitra Farahani (2006; Butimar Productions).