Biography

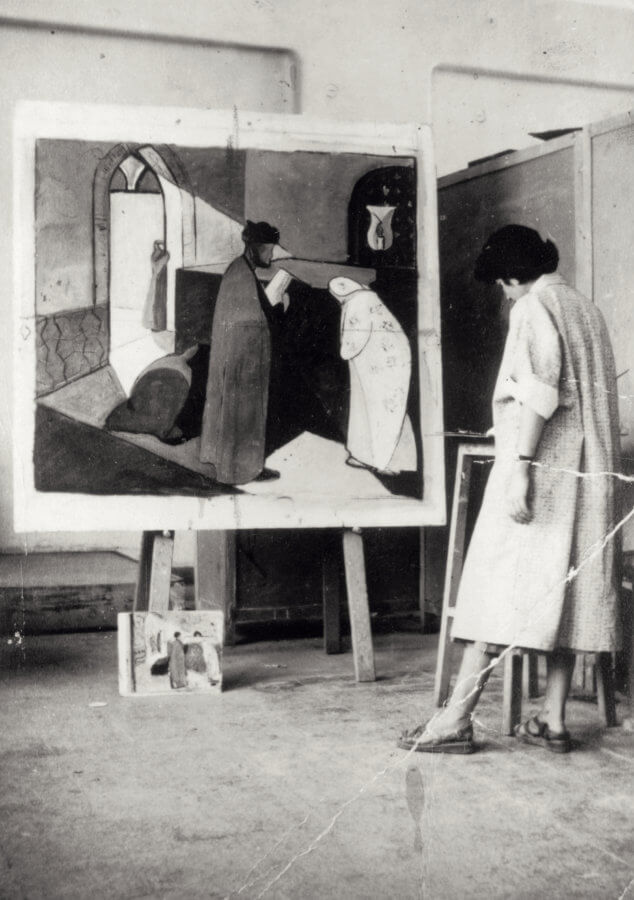

Behjat Sadr in the Fine Arts faculty painting studio at Tehran University

1954

Behjat Sadr in her studio, Tehran

1961

1. First month of the Muslim calendar: on the tenth day, Shi’a Muslims observe Ashura, a day of mourning commemorating the martyrdom of Imam Husayn.

2. Temporary or permanent religious edifice to commemorate the Day of Ashura.

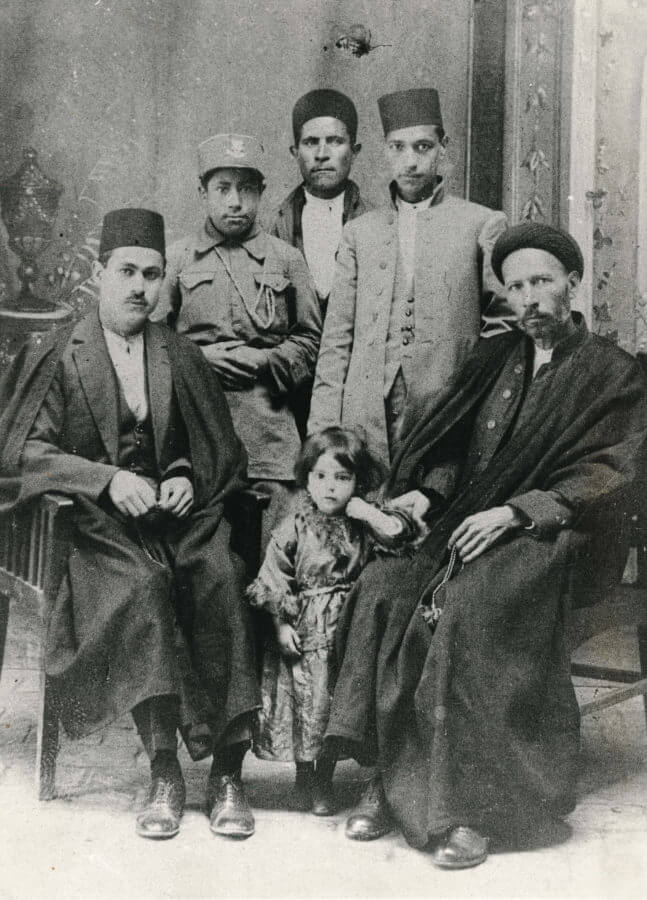

1924

Behjat Sadr Mahallati is born on 29 May, 1924, in Arāk (Iran), in a large, reconstituted family. She is the daughter and first child of Ghamar Amini and Mohammad Sadr Mahallati. Her father is a clergyman working at the Ministry of Justice, fond of poetry, calligraphy, and music. Her mother is an open-minded, attentive woman. Her paternal uncle is Mohsen Sadr Mahallati (Sadr ol-Ashraf), a former Minister of Justice and Prime Minister. Due to her father’s work, her family lives in various towns before settling in Tehran, and is respectful of traditions. The Muharram1 rituals are celebrated in a Tekyeh2 erected each year in their courtyard. Behjat Sadr will keep vivid memories of these periods, where massive crowds would gather in these Tekyehs, and of the subsequent encounters between young men and women.

3. He established the first private painting class for women in Tehran in 1940.

1931-1947

Primary and secondary studies in Tehran. Her father dies prematurely in 1934, and her family faces economic hardships that worsen with World War II. She learns silk crafts with a “Gypsy” woman after an art teacher discouraged her from being a painter, considering she had no talent for it. She chooses to train as a teacher. After these studies, in 1943, she becomes a secondary school teacher in order to be financially independent and to support her family. She starts taking an interest in painting, and joins Ali Ashgar Petgar’s3 painting classes in 1947.

1948-1954

Studies painting at the Fine Arts faculty at the University of Tehran while working as a secondary-school teacher. The university buildings also house the architecture, design and visual arts sections, so she comes into contact with an interdisciplinary environment and a vast array of techniques. In the Fine Arts faculty, she meets Sadegh Hedayat, then a librarian at the University of Tehran, and, more importantly, fellow students Sohrab Sepehri and Nasser Assar, with whom she creates a group with the aim of extending their academic curriculum through experimentation. In 1948, she marries writer Abolhassan Sadr, a distant cousin, before leaving him five years later. She graduates from her studies with full marks and honours.

Behjat Sadr with her husband, Morteza Hananeh, Rome

Late 1950s

Graduation party, Fine Arts faculty of Tehran University

1954

4. Giuseppe Sciortino, “Stranieri alla Biennale”, La Fiera letteraria,

15 of July 1956.

1955-1959

Goes to Italy in 1955 thanks to a grant from the Italian government and continues her art studies at the Rome Academy, following Roberto Melli’s painting class for grant recipients. She then continues her studies at the Naples Fine Arts School with Antonio Corpora and Armando Gentilini as teachers.

Early on in her stay in Rome, Behjat Sadr befriends Forough Farrokhzad, a great Iranian poetess quite unknown at the time, with whom she shares a whole universe of words and images.

In 1956, she is awarded the San Vito Romano prize and participates in the Venice Biennale. Although there is not yet an Iranian pavilion at the Biennale, Marco Grigorian manages to present a number of works by a few Iranian artists in the Italian pavilion. Behjat Sadr presents a still life that is noticed by Giuseppe Sciortino, who describes it as “delicate and post-impressionistic” 4.

She graduates from the Fine Arts School of Naples in November 1958. As early as her first year in Italy, she develops a personal style, a non-geometrical abstraction made of interplays of colour spots and traces that she presents in several individual and collective exhibitions. This is the time when she decides to stop painting on an easel, as she recalls: “I was entering an unconscious trance, applying paint pots and scrapers to my large canvas laid out on the floor.”

In 1957, Roberto Melli introduces her at Il Pincio gallery, which shows her work. Several renowned critics, intellectuals and art historians, among them Emilio Villa, Lionello Venturi, Guilio Carlo Argan and Pierre Guéguen, contribute to introducing her to the Rome art scene. Lionello Venturi, a critic and modern art professor at the University of Rome, introduces her to La Bussola gallery, where she will also show her work. In 1958, she marries Iranian composer Morteza Hananeh in Rome. This passionate marriage will last only seven years, but she will remember it forever. Several years after Morteza Hananeh’s death in 1989, she writes in her notes: “Hananeh is dead and everyone is dead.”

She tries to stay in Rome after the end of her studies, but her student grant is coming to an end. In September 1959, she is appointed as an associate professor in the Fine Arts faculty at the University of Tehran, and goes back to Iran.

1960

During the summer of 1960, she stays in Rome again before definitively settling in Tehran. The same year, one of her paintings is selected for the second-issue cover of the magazine Aujourd’hui (no. 27).

1961-1966

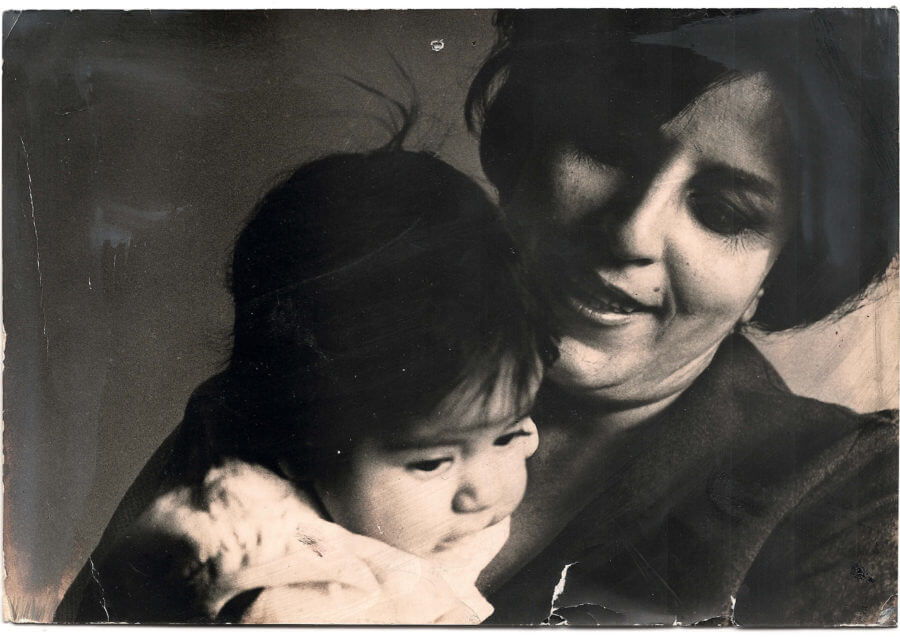

Develops a more gestural painting, with sturdier shapes on large formats, and participates in many international exhibitions. In 1962, she is awarded the 3rd Terhan Biennale Imperial Prize with Charles Hossein Zenderoudi. The jury is composed of Guiulio Carlo Argan, Frank Edgar, Jacques Laissaigne and Pierre Restany among others. She creates two monumental ceramic mural works in relief for the Hilton hotel façade (90 sq metres). The same year, she participates for a second time in the 31st Venice Biennale, and the next year in the São Paulo Biennale. She is made guest of honour at the 4th Tehran Biennale in 1964. Her only child Mitra (nicknamed Kakooti) is born in January 1964.

1967-1968

Creates a series of optical and kinetic works. The series is widely criticised at the time, and very few pieces remain today. Some of the works were equipped with engines and produced repetitive movements, creating plays of light or activating electric blinds. She is awarded the first prize in the Unesco painting competition against illiteracy, with a work called Light of Knowledge, whose red, minimalistic sun is revealed behind imposing blinds.

Forough’s sudden death in 1966, in a car crash, leaves her mourning someone she considered the truest woman, devoid of the slightest artifice. In 1986, she writes in her notes: “One thing I’m proud of in my life is my friendship with Forough, and how highly I valued her.”

Stays in Paris for a sabbatical year, and works with Gustave Singier at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, wanting to develop a method for art teaching. She witnesses the 1968 riots in the city. She recalls the day when she was sitting at the Select café with her artist friends Bahman Mohasses and Hossein Zenderoudi. She says she felt a sudden burst of anxiety and asked her friends to leave. They learned there was an explosion soon after their departure.

Behjat Sadr and her daughter Mitra, aged 3 months

1964

1969-1979

Further develops the experimental aspect of her work. She becomes the director of the Visual Arts Department at the University of Tehran. Her work is featured in the fourth volume of L’Art abstrait (Michel Ragon, Michel Seuphor, Maeght, 1974).

Second sabbatical year in Paris in 1974–1975: a fruitful, intensely productive year where she extends her visual field of investigation. Her subsequent works bear traces of the experiments conducted during this period. She creates works on aluminium. She lives through and attentively observes the Revolution and the changes it brings to Iranian society. The years 1974 to 1979 arguably make up her painting’s richest and most accomplished period. Afterwards, she will almost never paint in large format again.

1980-1990

permanently while regularly visiting Iran. From 1980, unable to work on large formats, she nevertheless continues her practice by creating photomontages and “photo-paintings” in smaller formats. She presents her works several times in individual and collective exhibitions. The period of these collages also reveals her practice as a photographer. Indeed, for compositional purposes, she cuts fragments of her own photographs (taken during trips in the forest or by the banks of the Seine, natural or architectural patterns) which she combines with various elements, including traces of paint.

Portrait of Behjat Sadr

Late 1960s

Behjat Sadr and her father (right)

1991-2003

She is faced with more health problems. She continues her small-format works but progressively spends more time on writing daily notes of her thoughts and observations. She records everything. Some of her folders also include drawings. Several dozen of these folders of writing and drawing remain from this period. She presents a set of her works at the Niāvaran Cultural Centre in Tehran in 1994 and in a retrospective at the Cité des Arts in Paris in 1999. She takes part in several major collective exhibitions.

2004

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art pays tribute to her with a vast retrospective exhibition of her work as part of a series of exhibitions devoted to the pioneers of modern art in Iran. A documented monograph retracing her career is published for the occasion.

2005-2009

Faces more serious health problems, followed by a series of hospitalisations. In spite of this, she seizes every opportunity to draw and continues to write intensely. She takes part in several collective exhibitions.

2009

On 10 August, she passes away due to heart failure in Corsica, while swimming in the sea. In the summer of 1991, she wrote in her notes (folder 36): “I like the sea more than the earth. In the earth, one ends up buried. At sea, one is immersed, as one is immersed in joy, in beauty, in happiness, in delirium, in work. . . .The earth has mountains, hills, crevices, while the sea is endless, driving the eyes towards infinity.”